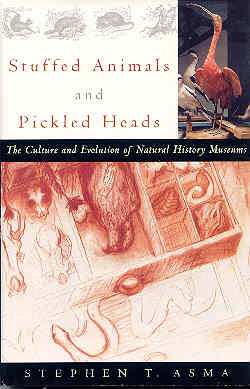

Stuffed Animals and

Pickled Heads

Stephen Asma

Once again, the book under consideration this month has a most intriguing title! As with Noodling for Flatheads, how could any reader pass up a book called Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads? Not this editor or printer, you may be sure.

As it turns out, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads is subtitled The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums, and in it writer Stephen Asma presents a fascinating look the subject, from some of the earliest (and rather grisly) exhibits at Peter the Great's court in eighteenth century Russia, to the present-day taste for animated dinosaurs and the like.

While the staff of the Newswire realizes that not all its readers may be enthusiastic museum-goers, Pickled Heads certainly presents a strong case for visiting one or two. This editor, for instance, can hardly wait for her next trip to London (or Paris, for that matter), in order to check out some of the collections Asma described in the book.

Consider this passage from the beginning of Stuffed Animals:

"Collecting and displaying natural history specimens is a more complex and dramatic activity than most museum visitors appreciate. The specimens themselves, for example, have intriguing and elaborate histories that largely go untold, because, unlike fine art objects, their individuality must be subjugated to the needs of scientific pedagogy. Generations of visitors at the American Museum of Natural History, for example, examined an Inuit skeleton as part of a general anthropology exhibit, unaware of the skeleton's own peculiar history.

In 1993 the American Museum of Natural History finally returned this particular skeleton, the remains of an Inuit man named Qisuk and other Inuits, to his descendants in western Greenland. Qisuk and other Inuits, including his six-year-old son, Minik, had been "acquired" as living specimens during an Arctic expedition in 1897. After polar explorer Robert Perry convinced the Inuits to return with him, the new emigrants found themselves housed in the basement of the American Museum of Natural History. Shortly after arriving, Qisuk died of tuberculosis, and unbeknownst to Mini, the museum staff removed Qisuk's flesh, cleaned his bones, and put him on display for New York audiences. Some time later Minik, who originally had been told that his father's bones had been returned home for proper burial, stumbled across his own father in an exhibit display case."

Asma goes on to relate his curiosity about preservation techniques (we'll spare you the details of those!), and his growing interest in, as the subtitle tells, the evolution of natural history museums. In his travels from New York to London to Paris, and on to St. Petersburg, he presents a fascinating look at how natural history museum displays and philosophies have changed over the years, how they reflect our changing tastes in what museums should show and tell us, and how those institutions teach us what they teach. In the end, natural history museums and their displays are a reflection of their audiences, a window into our view of ourselves and the world we share with so many other creatures.

Until next month, be sure to Read All About It.

All Rights Reserved.