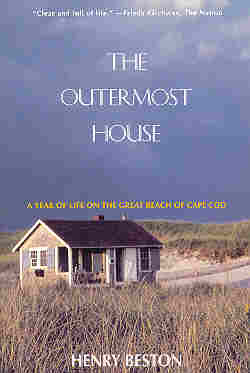

The Outermost

House

Henry Beston

“Our fantastic civilization has fallen out of touch with many aspects of nature, and with none more completely than with night. Primitive folk, gathered at a cave mouth round a fire, do not fear night; they fear, rather, the energies and creatures to whom night gives power; we of the age of machines, having delivered ourselves of nocturnal enemies, now have a dislike of night itself. With lights and ever more lights, we drive the holiness and beauty of night back to the forests and the sea; the little villages, the crossroads even, will have none of it. Are modern folk, perhaps, afraid of the dark? Do they fear that vast serenity, the mystery of infinite space, the austerity of stars? Having made ourselves at home in a civilization obsessed with power, which explains its whole world in terms of energy, do they fear at night for their dull acquiescence and the pattern of their beliefs? Be the answer what it will, to-day's civilization is full of people who have not the slightest notion of the character or the poetry of the night, who have never even seen night. Yet to live thus, to know only artificial night, is as absurd and evil as to know only artificial day.”

The paragraph above comes from Henry Beston's lovely and lyrical book, The Outermost House. Long recognized as a classic of American nature writing, this chronicle of a solitary year spent on a Cape Cod beach was first published in 1928. It continues to attract readers, and has not been out of print from that time to this. The author continues:“Night is very beautiful on this great beach. It is the true other half of the day's tremendous wheel; no lights without meaning stab or trouble it; it is beauty, it is fulfillment, it is rest. Thin clouds float in these heavens, islands of obscurity in a splendor of space and stars: the Milky Way bridges earth and ocean; the beach resolves itself into a unity of form, its summer lagoons, its slopes and uplands merging; against the western sky and the falling bow of sun rise the silent and superb undulations of the dunes.”

Despite the frequent quotation of his works by the conservation movement, Beston was not an original environmental thinker in the sense that Aldo Leopold was, or Rachel Carson. He thought of himself as a writer rather than a naturalist, and was an extremely conscientious and meticulous craftsman. Consider the following lines:

“We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.”

In The Outermost House can be found many of the wonders of life – the migrations of shore and sea birds, the ceaseless rhythms of wind and sand and ocean, the pageant of stars in the changing seasons. Beston's words capture the vividness of nature and bring the reader that much closer to understanding humanity's true relation to the cosmic picture. Be sure to read all about it.

All Rights Reserved.