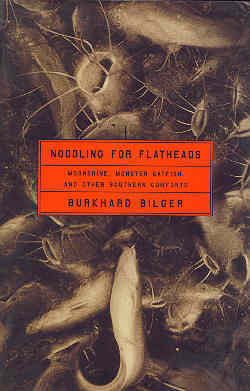

Noodling for Flatheads

Burkhard Bilger

"By now Lee's eyes flash signals clearly as a lighthouse: He's found a big one. In a beat I'm crouched next to him, arms tangled with his inside the den, hands splay-fingered to stop the fish's charge. Somewhere in there, a fish is caroming off the sides of the barrel, ringing it like a muffled gong. And I realize, with a shudder, that my fingers are waving frantically, almost eager for a bite.

'He's on your side,' Lee yells. 'Can't you feel him?'

No. But how could I miss such a huge fish? A twitch of my right hand solves the conundrum: I can't feel the fish, it seems, because my arm is all the way down its throat. The fish and I realize this at the same time, like stooges backing into each other in a haunted house. The fish clamps down, I try to yank free, and the rest is a wet blur of thrashing, screaming, and grasping for gills. At some point Lee threads a rope through its mouth, and for just a second I get a good look at an enormous, prehistoric face. Then with a jerk of its shoulders, it wrenches free, taking a last few pieces of my thumbs with it."

As the above passage from Noodling for Flatheads – Moonshine, Monster Catfish, and Other Southern Comforts, by Burkhard Bilger, demonstrates, even today there is a lot of American culture that isn't as predicable as it seems.

In eight essays, Bilger manages to give his readers a glimpse of various Southern customs that survive on the fringes of society. In doing so, he poignantly presents the case that these folk traditions add richness and depth to today's increasingly homogenized world. While the practices presented seem quirky (after all, who would have thought of "noodling for flatheads": catching catfish by getting them to bite your hand), Bilger successfully relates them through first-hand encounters, never condescendingly, but with a real respect for the people who practice them.

Besides noodling, there are essays on a visionary frog farmer, coon hunting, marbles tournaments, and, of course, soul food.

None of these essays is intended to revitalize dying traditions, just to record them. As Bilger writes: "Better to let a tradition run its course – to die of natural causes or disappear in the thicket of popular culture.... I mean, when some eighteen-year-old city kid plays 'Whoa, Mule, Whoa,' what does that mean to him? Not the same as to Grampa who had to hold onto that mule. Not the same as to that old red-faced man standing up there laughing and signing it, looking around for a glint of recognition in his audience."

Until next month, be sure to Read All About It.

All Rights Reserved.